Executive Summary

SAAD Organization, in partnership with MOWDAFA and with support from GIZ, conducted a three-day intensive training for 54 university students from Green Hope University, Qardho, on Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and other forms of Gender-Based Violence (GBV). The training aimed to equip youth with the knowledge to critically reflect on FGM, its health risks, and its status as a human rights violation. Using participatory methodologies including case studies, group work, and role-playing, the training achieved significant knowledge gains. Pre- and post-test results demonstrate a marked improvement in participants’ understanding of FGM types, negative health consequences, and underlying drivers, highlighting the intervention’s effectiveness in building a foundation of youth advocates for FGM abandonment in Puntland

1.0 Background

Smart Aid and Development Organization (SAAD) is a non-profit, community-based organization established in February 2015 in Puntland State of Somalia. For the past four years, SAAD has effectively collaborated with Puntland Ministry of Women Development and Family Affairs (MOWDAFA) on FGM prevention, playing an active role in improving community-level awareness and commitment to ending this harmful practice

1.1. Introduction

Somalia has the highest global prevalence of FGM, with an estimated 80-90% of cases being the most severe form, Type III (infibulation).[1] This practice poses serios immediate and long-term health risks for mutated girls, as well as other complications in childbirth and increased risk of newborn deaths. Moreover, FGM constitutes a severe violation of human rights.[2] SAAD Organization, in collaboration with the Puntland Ministry of Women Development and Family Affairs (MOWDAFA), with support of GIZ, conducted a three-day intensive training for Green-Hope University students on Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and other forms of Gender-Based Violence (GBV). The training was held at the Alle Amin Hotel in Qardho on August 20-21, and 4th September 2025.

This training aimed to equip fifty-four university students from Qardho with the knowledge and skills to critically reflect on Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) as a harmful practice and accurately identify its associated health risks and human rights violations.

2.0 Training Objectives

The training was designed to achieve the following specific objectives. By the end of the session, trainees were expected to be able to:

- Reflect on harmful traditional practices from a global and local perspective.

- Generate a comprehensive definition of FGM and classify its types according to WHO.

- Identify the immediate and long-term health risks associated with FGM.

- Analyze the socio-cultural and religious myths underpinning FGM in Puntland.

- Evaluate FGM as a human rights violation.

[1] Gele et al.: Have we made progress in Somalia after 30 years of interventions? Attitudes toward female circumcision among people in the Hargeisa district. BMC Research Notes 2013 6:122.

[2] World Health Organization. “Female Genital Mutilation.” WHO, 31 March 2024, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation.

3.0. Methodology:

The training used a mixed learning approaches including:

Pre- and Post-Tests: To quantitatively measure knowledge gain among participants.

Formal Lectures: For delivering the essential facts about FGM; definitions, types, and health consequences.

Case Study Analysis: Examining global traditional practices (e.g. Foot-binding in China and Lip Plates in Ethiopia) to encourage critical thinking about harmful traditional practices.

Group Discussions & Brainstorming: To explore local drivers of FGM and brainstorm context specific solutions.

Group Work: Categorizing health risks into immediate and long-term risks of FGM as well as obstetrical complications.

Role-Playing: Practicing the delivery of selected awareness raising messages where students played different roles in community awareness.

4.0 Description of the Activity

4.1 Opening Ceremony

The event was inaugurated by key stakeholders on 20th August 2025: Ms. Sahra Jaqanaf, Coordinator of the Ministry of Women Development and Family Affairs (MOWDAFA) for Karkar region; Mr. Jim’ale, the Green Hope University Principal; and Mr. Burhan Mohamed, Executive Director of SAAD Organization.

All three speakers underscored the significance of the program and how high they expected from the participants.

- Ms. Sahra Jaqanaf (MOWDAFA) detailed the ministry’s dedication to eradicating Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). She expressed her hope that the youth would lead the struggle against the practice in the future. She extended her thanks to SAAD Organization, GIZ and University management for their collaborative efforts in making the training possible.

- Mr. Jim’ale (University Principal) welcomed participants and emphasized that Green Hope University is committed to raising community awareness on public health issues. He stated that education on critical issues like FGM is an integral part of the institution’s duty to society.

Mr. Burhan Mohamed (SAAD Organization) expressed his gratitude to the youth participants, acknowledging their role as future change-makers. He underlined the necessity of community ownership, stating,

“ The ultimate responsibility to stop the practice lies with the community itself. This is not a short-term mission but a lifelong dedication to the goal of eliminating this harmful traditional practice. ”

4.2. Pre-Test Assessment

Following participant registration, a pre-test was administered to establish a baseline understanding of participants’ knowledge. The assessment focused on three key dimensions:

- The types of FGM practiced in the Qardho district and participants’ personal views on each type.

- Awareness on the negative health consequences associated with FGM.

- The reasons why communities perform the practice.

After the training, participant responses were analyzed per question. All answers were translated into English and compiled into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Unique responses were recorded, and recurring answers were tallied. Similar answers were grouped into thematic categories, and frequencies were used to calculate percentages based on the total number of participants.

4.3. Sessions Delivery

Session I: Understanding Female Genital Mutilation

A. Examining Harmful Traditional Practices

After the pre-test, the facilitator introduced two historical and cultural case studies of harmful traditional practices for group discussion:

- Foot-binding in China: The practice involved the tight wrapping of the feet of Han Chinese girls to inhibit foot growth, often breaking bones. It was a symbol of beauty and high social status, believed to lead to better marriage. However, it caused lifelong pain and physical impairment and was finally banned in 1912.[1]

- Lip Plates among the Mursi: When a Mursi girl reaches puberty, her lower lip is cut and stretched over time to accommodate increasingly larger clay or wooden plates. This signifies her transition to womanhood and is tightly linked to fertility and eligibility for marriage. The practice can lead to chronic infections, gum damage, tooth loss, and difficulties with eating and speaking.[2]

Students were then asked to reflect on these traditions: Are they valuable cultural practices to be preserved at all costs, or are they unnecessary harmful practices that could be abandoned? If those communities were to listen to you, would you recommend they stop these practices?

Participants engaged in a thorough discussion. All the participants 100% viewed these traditions as harmful and told that they would recommend stopping them.

B. Introducing Female Genital Mutilation

Finally, female genital mutilation was presented describing it as ” partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for nonmedical reasons”. In the local context, the practice involves removal of clitoris and parts of labia minora and labia majora, and to stop the bleeding the resulted wound is often sewn shut with thread, leaving a very small opening for urinating and menstrual blood. Deeply rooted in cultural beliefs about purity, chastity, and maturity, FGM is viewed as essential for preparing a girl for adulthood and marriage, ensuring her honor, and it is widely perceived as a religious requirement. This practice offers no health benefits to the girl and is linked to severe detrimental health consequences.”

Participants were then asked to reflect on this practice using the same critical lens applied to the previous two examples. Although, some participants showed defense, the majority agreed that FGM particularly infibulation is comparable to foot binding and lip-plating practices, and they would recommend stopping it.

C. Types of Female Genital Mutilation in the Local Context

After introducing the WHO definition of FGM and its types (type 1-4)[3], participants were asked to reflect on the local context (Sunna and Pharaonic). They described the Sunna female circumcision as a procedure ranging from a minor clitoral injury to its partial removal, which may or may not involve suturing. Typically, the cut clitoris is stitched with one to three suture points as participants described. If the wound is stitched once or not at all, it is called Sunna Saqiir, while if it is stitched twice or thrice is called Sunna Kabiir. Some added another bizarre version of Sunni circumcision practiced by internally displaced people; clitoris is cut along with parts of labia minora, then the wound is connected sewing the labia majora which are not cut, after days, the suture is removed resulting narrowed vaginal opening. They call as part of the Sunna type. Pharaonic female circumcision is a typical infibulation (type 3 WHO classification) as described by the participants. The clitoris is removed, then parts of labia minora and labia majora are removed, the resulting wound is sewn using thread or medical sutures.

After participants classified and described the female cuttings practiced in Qardho and nearby villages, they were asked to compare them with WHO classification of FGM and which one is most prevalent in their city. They all agreed that pharaonic circumcision is type 3 FGM (infibulation) which more common in rural areas and IDPs camps. However, Sunni type varies and could fit in all WHO types as seen in their description.

Session II: Exploring the Health Consequences of Female Genital Mutilation

To deepen participants’ understanding of the health implications of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), an interactive group activity was designed using materials adapted from a World Health Organization (WHO) document. The content—which outlined various FGM-related health complications—was translated into Somali and organized into three categories:

- Immediate health consequences

- Long-term health consequences

- Childbirth complications

Each complication was printed on a separate slip of paper. Participants were divided into small groups and provided with these slips. They were then asked to collaboratively classify each health risk into one of the three categories, recording their answers on sticky notes and placing these on flip charts.

[1] Chowdhury, Laura & Zhang, Yile & Nichols, Ryan. (2022). Footbinding and its cessation: An agent-based model adjudication of the labor market and evolutionary sciences hypotheses. Evolution and Human Behavior. 43. 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2022.08.005.

[2] https://www.mursi.org/documents-and-texts/published-articles/shauna-latosky/the-lip-plates-of-mursi-women

[3] World Health Organization. “Female Genital Mutilation.” WHO, 31 March 2024, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation.

This task encouraged critical thinking and group discussion. Following the classification, each group presented and explained their choices to the larger audience. A rotational peer-review format was then used: groups examined each other’s flip charts, asked questions, and provided written feedback. This allowed participants to engage critically with different perspectives and refine their understanding through dialogue

After the group activity, the facilitator reconvened the participants for a plenary session. Using medical research and expert sources, the facilitator reviewed the complications, clarified misconceptions, and highlighted evidence-based facts about the health impacts of FGM

The table below summarizes the negative health consequences of FGM as discussed during the session:

| Immediate Health Risks | Longer-term Health Risks | Obstetric Complications |

|---|---|---|

| Severe pain | Need for surgery | Caesarean section |

| Shock | Urinary and menstrual problems. | Postpartum haemorrhage |

| Excessive bleeding | Painful sexual intercourse | Extended maternal hospital stay |

| Difficulty in passing urine | Infertility | Infant resuscitation |

| Infections | Chronic pain | Stillbirth or early neonatal death |

| Death | Reproductive tract infections | |

| Psychological consequences | Psychological consequences | |

| Unintended labia fusion |

Session III: Analyzing the Roots

A. Why Does FGM Persist?

The second session of the training engaged participants in a critical examination of the social, cultural, and religious factors that perpetuate FGM. The session began with a brainstorming discussion centered on the question: Why does FGM continue in our community?

Participants discussed in pairs and documented their thoughts on sticky notes. They pointed out the following:

- Social Pressure: “Mothers fear what other women in town may say if they hear she didn’t cut her daughter.”

- Normalization of Practice: “Girls cannot be left the way they were born; they have to be cut. That is what we do.”

- Religious Misinterpretation: “Circumcision is Sunnah” (suggesting a religious basis); “Uncircumcised women are barred from certain rituals, like touching the Holy Quran.”

- Control and Protection Narratives: “Girls are circumcised to be protected” (referring to the control of female sexuality); “Men don’t want to marry an ‘open’ woman.”

- Cultural Tradition: “Circumcision is part of culture and tradition.”

- Lack of Awareness: “Lack of education and religious misconceptions are main causes.”

Following the discussion, the facilitator presented materials developed by SAAD Organization and MOWDAFA under the GIZ FGM Prevention Program. These included a video in which Sheikh Abdulkadir Diriye Adam clarified Islamic perspectives on FGM, and Dr. Habiba, an obstetrician-gynecologist details the health consequences of the practice. Samsam Diriye, representing MOWDAFA GBV department also affirmed the Puntland government’s zero-tolerance and anti-medicalization policies, and the Puntland FGM Bill Act.

Participants then engaged in a role-playing activity using anti-FGM awareness messages tailored to address religious, cultural, health, and human rights aspects. For example, one participant embodied a doctor conveying the message, “An uncut girl is healthier than a cut girl,” to a young man who believed FGM promoted cleanliness.

To further dissociate FGM from religion, the facilitator presented evidence from the Shafi’i school of jurisprudence—followed by most Somalis—and invited participants to reflect on whether harmful practices like FGM can be religiously justified. Key clarifications included:

- Quranic Silence: There is no mention of female circumcision in the Quran.

- Lack of Authentic Hadith: No reliable hadith explicitly commands FGM.

- Invalid Analogy with Male Circumcision: Anatomical and physiological differences make analogies between male and female circumcision illogical and religiously untenable.

- Absence of Scholarly Consensus: Opinions among Islamic scholars vary widely from obligatory to discouraged, and many respected scholars reject the practice entirely, especially in light of medical evidence.

B. FGM Violates Human Rights

The session concluded by framing FGM as a violation of human rights: it inflicts severe physical and psychological harm, violates bodily autonomy, discriminates against women and girls, and contradicts the principles of dignity and health

5. Results of Pre-test and Post-test Assessments

A comparative analysis of pre- and post-test results demonstrates a significant improvement in knowledge and critical awareness among participants

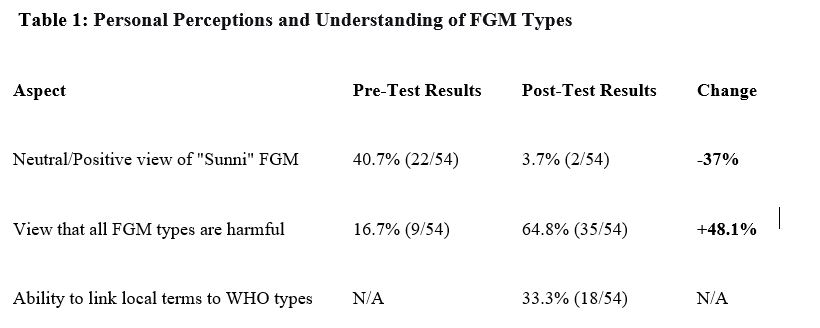

5.1. Personal Perceptions of FGM

In the pre-test, all participants classified FGM types into “Sunni” and “Pharaonic.” A significant portion (40.7%, 22/54) expressed neutral or positive views toward “Sunni” FGM, perceiving it as medically benign (7.4%), religiously endorsed (13%), or culturally appropriate (16.7%). Approximately one-third (33.3%, 18/54) identified “Pharaonic” FGM as harmful or a violation, while 16.7% (9/54) recognized that all forms of FGM are harmful or violate human rights.

In the post-test, 33.3% (18/54) of participants successfully connected local terms (“Sunni”/”Pharaonic”) with WHO classifications (Types I/II and III). A significant shift occurred in recognizing FGM as harmful: 29.6% viewed all types as harmful, 14.8% identified them as human rights violations, and 20.4% acknowledged all forms as harmful while emphasizing the severity of infibulation. Combined, 64.8% demonstrated improved awareness. However, 3.7% (2/54) still considered “Sunni” FGM acceptable for religious reasons.

The training was highly effective in challenging the misconception that “Sunni” FGM is acceptable, with a 37% reduction in this belief and a 48.1% increase in the understanding that all forms are harmful. See Table 1 below:

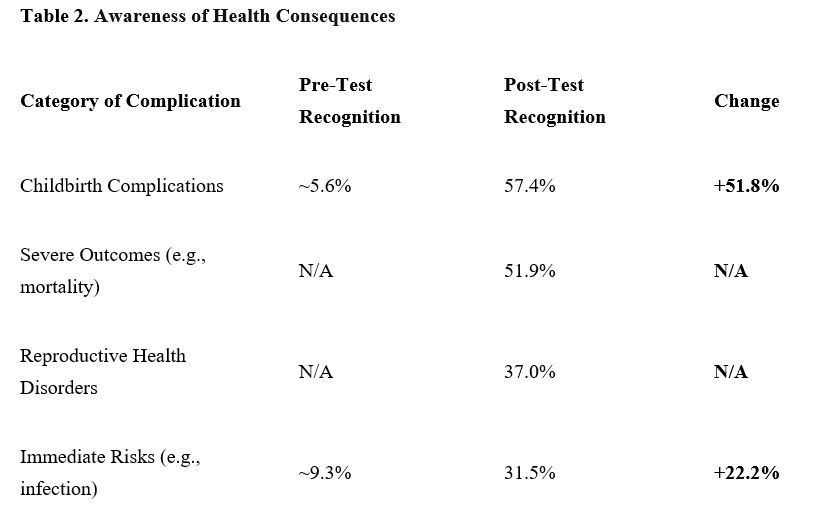

5.2. Health Consequences

In the pre-test, only 9.3% (5/54) recognized all types of FGM as harmful with no health benefits. However, 50% (27/54) identified at least one health complication, such as bleeding during cutting (9.3%), childbirth issues (5.6%), or sexual dysfunction (5.6%). Nearly 10% held dangerous misconceptions that “Sunni” FGM is harmless or acceptable if performed “correctly,” while 5.6% linked FGM to gender-based violence.

In the post-test, participants showed improved awareness: 57.4% identified childbirth complications (e.g., bleeding, induced labor, cesarean sections), 51.9% recognized severe outcomes (e.g., maternal/infant mortality), 37% understood reproductive health disorders (e.g., infertility, dysmenorrhea), and 31.5% acknowledged immediate risks (e.g., infection, shock). However, 16.7% retained misconceptions about “Sunni” FGM being less harmful, indicating a need for continued focus.

Participants showed dramatically improved knowledge across all categories of health risks, particularly regarding obstetric and severe outcomes as shown in Table 2.

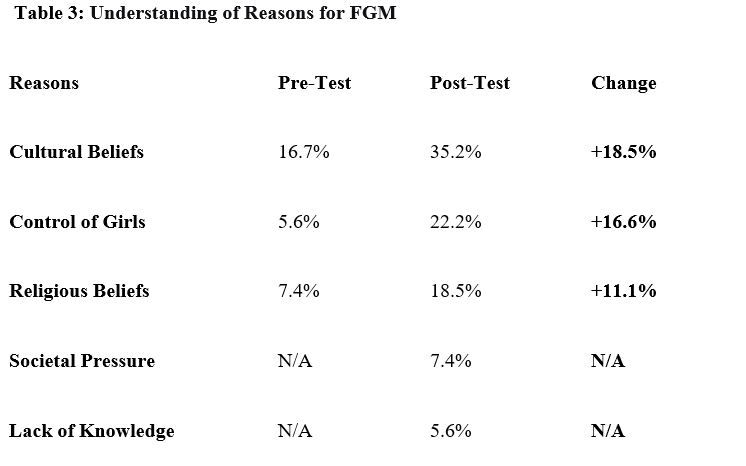

5.3. Reasons for FGM

In the pre-test, cultural beliefs were the most cited reason (16.7%), followed by religious beliefs (7.4%). Traditional norms, marriageability, and protecting girls’ virginity were each cited by 5.6% of participants.

In the post-test, cultural beliefs remained the dominant factor (35.2%), but new insights emerged, such as controlling girls’ bodies (22.2%) and religious beliefs (18.5%). Participants also recognized traditional norms (11.1%), marriageability (9.3%), societal pressure (7.4%), lack of knowledge about FGM’s harms (5.6%), and misconceptions linking FGM to cleanliness/beauty (3.7%).

Post-test responses revealed a more nuanced understanding, with participants identifying more structural and gender-based drivers like control and societal pressure, alongside persistent cultural and religious factors.

6.0 Challenges and Unexpected Outcomes

- Gender Imbalance: Majority of participants were female students, as FGM is predominantly perceived as a “women’s issue”.

- Participant Identification: The high number of participants wearing veils (niqabs), while fully respected, presented a practical difficulty for facilitators in consistently recognizing and individually engaging students across sessions, potentially affecting the depth of personal connection.

- Local Perception: Despite the progress made, 16.7% of participants retained some misconceptions about the harm of Sunni female circumcision. The Sunna type of FGM is not widely recognized as harmful or even as a form of FGM in the local context, presenting a significant barrier to abandonment. Participants found it challenging to clearly connect the varied local practices (“Sunni Saqiir/Kabiir”) to the WHO types of female genital mutilation.

7.0 Lessons Learnt

- Effective Facilitation Methods: Case studies and role playing proved to be very effective ways in building higher thinking skills among students in sensitive topics like FGM.

- Need for Male Engagement: Future recruitment must proactively target male students through tailored messaging that frames FGM as a community health and human rights issue affecting everyone, not solely a women’s issue.

- Adapting Facilitation Techniques: in the following activities, facilitators will use more personalized name tags and implement small-group activities with fixed members to foster stronger connections and ensure consistent engagement, respecting cultural dress norms.

- Sunna-Specific Messaging is Critical: The data confirms that deconstructing the myth of Sunna FGM must be the central pillar of all awareness campaigns. This requires continuous collaboration with religious leaders and medical professionals to amplify a unified message.

8.0 Conclusion and Way Forward

The training successfully achieved its objectives, significantly improving participants’ knowledge and critical perception of FGM. The results demonstrate a successful model for youth engagement on sensitive topics.

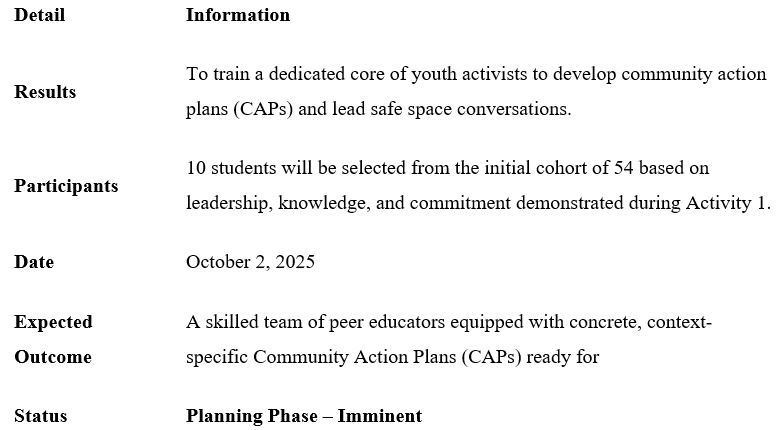

The immediate next step is to capitalize on this momentum by investing in a dedicated core of activists from the trained cohort.

Activity 2: Advanced Training for Youth Activists- Upcoming

This advanced training will focus on practical skills in advocacy, community mapping, CAP development, and facilitation techniques. This core group will be essential for scaling the impact of the project and ensuring its sustainability beyond the initial training. SAAD extends its gratitude to GIZ for their steadfast support and to MOWDAFA and Green Hope University for their invaluable collaboration in making this initiative a success

Prepared by:

Ahmed Isse, Project Officer

Smart Aid and Development Organization

20 September 2025